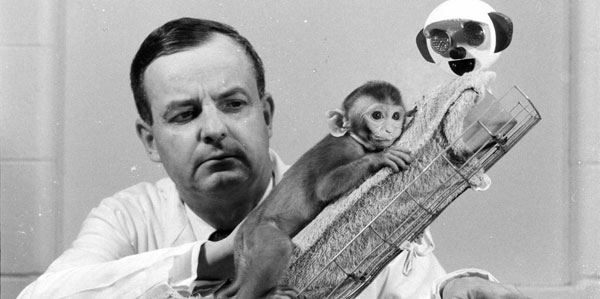

In 1949, Harry F. Harlow conducted an experiment that forever changed our understanding of human behavior. The test was done on eight rhesus monkeys. For two weeks, the monkeys were tasked with solving a mechanical problem that required them to pull out a vertical pin, undo the hook, and unhinge the cover. There was no incentive or reward for the monkeys to finish the puzzle.

To Harlow’s surprise, the monkeys performed exceptionally well. Within two weeks, all eight had completed the challenge. Two thirds were able to complete it under 60 seconds. During this period, the monkeys received no instruction on what to do. They didn’t receive food or water for completion. There was no pressure to engage with the experiment at all. They simply did it because they wanted to.

Harlow’s team decided to add another layer to the experiment. In a second trial, they decided to motivate the monkeys using a food reward. Successful trials would award the monkeys with raisins. Here’s where things got interesting: The added incentive didn’t improve task performance. It actually made it worse. Monkeys made more errors. They solved the problem less frequently. Instead of being a supplement to positive behavior, the raisins actually seemed to become a distraction. This didn’t just puzzle Harlow. It baffled him.

Just imagine if he knew we were still making this same mistake 70 years later.

Up until Harlow’s experiment, motivation behind human behavior had been drilled down to two things: 1) Biological (e.g. satisfying urge for hunger, thirst) and 2) External (e.g. punishment and incentives). People either do things because it’s beneficial for survival, or because someone else incentivized us – i.e. carrots and sticks. Here’s the problem: Neither explained the behavior of Harlow’s monkeys. In fact, the monkeys actually argued the opposite. Adding the external incentive of food made their ability to solve problems worse. If biological needs or external rewards didn’t facilitate the behavior of the monkeys, what did?

Left with unanswered questions, Harlow decided to come up with a new theory behind human behavior: Intrinsic reward. The eight monkeys were presented with a task problem that generated an intuitive interest for problem solving. This wasn’t a forced behavior. It was completely organic. This kind of interest isn’t facilitated through biological needs or external rewards. It’s born from something we all intuitively have. It’s also the most powerful form of human motivation that exists.

That is – if we find a way to prevent others from stripping us of it.

…

When people first get into coaching, I think we all gravitate towards working with a desirable population of athletes. We don’t want to work with nine year olds. We want to be ground floor with elite athletes. We want to be in the same cage with top high school prospects, collegiate players, and professionals. The thought of working with a Little League player isn’t as exciting as working with a 21-year old SEC draft prospect. After all, kids don’t have the attention span to really handle elite level coaching – or at least our perception of what we think we can offer. I think it’s a horrible mistake.

As a private instructor, I’ve had the privilege of working with a wide range of athletes. Of these different populations, there’s one that I think all coaches need to have experience working with. It’s not professionals (you’d be surprised how many actually want coaching). It’s not college players. It’s not even high school players.

It’s kids.

Whenever I’m on the floor with kids 9-12 years old, I don’t see their presence as a burden. I view it as a privilege. The relationships you build are the epitome of a two way street: You need them as much as they need you. Working with kids forces you to get creative in ways that no other population demands. At the same time, kids need you to be their guide. They’re young and malleable. They’re very open to coaching and information, which at the same time makes them prone to bad information (see examples of this here and here). If you build a strong foundation early, you have the chance to get them going on a path that nurtures their long term development. The best way to do this is to cultivate what Harlow discovered back in 1949.

The most powerful weapon you can equip with kids isn’t a good swing or a beautiful arm action. It’s an insatiable desire to tap into their intuitive capacity for curiosity. We need kids who want to engage with the world in creative and meaningful ways. The best part is they already know how to. You don’t have to teach it. You just have to prevent other people from stripping it away.

Seth Godin – entrepreneur and best-selling author of Purple Cow, This is Marketing, and The Dip – believes all kids should learn two things:

- How to lead

- How to solve interesting problems

Let’s look at the second one: Solving interesting problems.

Harlow’s monkeys weren’t incentivized with food or water. They weren’t threatened with punishment, either. They were given an interesting problem. When faced with an interesting problem, people – and monkeys – are going to naturally try to solve it. We’re inherently curious. Just think about how a newborn baby interacts with the world. They know no rules or boundaries. The world is their playground. If they don’t understand something, they’re going to investigate it. There’s no second-guessing or thinking about the consequences for their decisions. They just simply see and do.

And then they’re taught the “rules” and “boundaries” of the world. Of all the words kids hear on a daily basis, there’s one that sticks out among the rest: No. Kids are always being told what not to do. Don’t touch this. Don’t go there. Don’t run. Don’t talk to them. Quite honestly, we find the natural curiosity of young kids intimidating. We see it as a loss of control, so we work hard to regain that control. This is the process through which we kill creativity. Kids no longer see opportunities for action. They see everything they cannot do. Kids aren’t dumb. If you’re constantly telling them not to do stuff, they’re going to pick up on it pretty quickly. They’ll avoid it – to your pleasure. This is where we make a huge mistake.

Kids need interesting problems to grow. Interesting problems are hard – as they should be. Coming to solutions requires a safe space where kids feel they can test new things, try out different ideas, and come to their own conclusions. They do not require our judgement. If you give a kid an interesting problem to solve, the worst thing you can do is tell them they are wrong. When you do this, you’re not giving them constructive feedback. You’re discouraging behavior that is critical to their long term development. Creativity cannot be cultivated when it’s constantly judged. It needs freedom. If kids don’t feel safe to creatively grapple with problems without consequences, they’re not going to. They’re going to avoid them the way they avoid green beans.

If we think about the learning environments most kids operate in, they don’t have room to express their creativity. It’s very black and white. You either memorized it or you didn’t. You either applied the formula correctly or you didn’t. Harlow proved back in 1949 that carrots and sticks are not an effective way to build problem solvers – yet that’s what we constantly try to do. Not getting the behavior you want? Let’s toss in an extended lunch for reward. Better yet, let’s dock them of recess time if they don’t. We think kids behave the same way we’d train our dogs. It’s completely backwards.

Curiosity cannot be cultivated through extrinsic rewards. It’s organic. It’s intuitive. Kids don’t need a system of rewards to learn how to do something new. They need opportunities to dive into things they find exciting. They need environments that encourage exploration without consequences. If they don’t get it right at first, they don’t need your judgement. They need encouragement. It’s not about being right. It’s about building a love for learning. This starts with a desire to continuously seek why things are the way that they are. You’re either feeding this or depriving it – consciously or unconsciously.

I think this is the biggest reason why I love working with kids: You can help them hold on to their curiosity. I love the feeling when a kid comes up to me with a question. Before I respond, I’ll always say: “That’s a really great question.” When we’re on the floor, I’ll constantly pull up film of big league guys. I’ll then show them their swings and say, “What do you notice about (insert big leaguer)’s swing? How does it compare to yours?” One day we might try to swing like Ronald Acuna Jr. Another day, we might try to swing like Fernando Tatis Jr. It doesn’t seem like traditional instruction, but a ton of learning is going on in these moments. You’re opening their eyes to different ways of doing things. This doesn’t just have a positive impact on their swing. It opens up their imagination.

The biggest thing you need to do, however, is change the narrative around failure. When you give kids problems and challenges that just exceed their ability, they don’t need to hear what they do wrong. They need to be encouraged to try again. Don’t reward ability. Don’t comment on how they compare to their peers. Simply reward their efforts for engaging with something that challenged them. We need to constantly build positive associations around behaviors that keep their curiosity in tact. If their intellect feels threatened, they’re not going to attempt it. That’s where we play a really big role as coaches. They might might have produced the desired result, but it’s not about the result. It’s the process they took to get there. This process must be fueled by their innate desire to understand the world. If you can get them to hang on to this, you have a chance to build a pretty special kid.

Don’t let kids become passive participants. Make them an active part of their development process. They have the most powerful form of motivation that exists on this planet. Tap into it and use it to your advantage. Most of us have to work hard to get back into a state of mind where we’re naturally curious about the world and why things are the way that they are.

The best way to do this is to never lose it.