The fourth quarter of the 1991 NBA Finals was about to begin. Magic Johnson’s Los Angeles Lakers and Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls were deadlocked at 80 in a decisive game five.

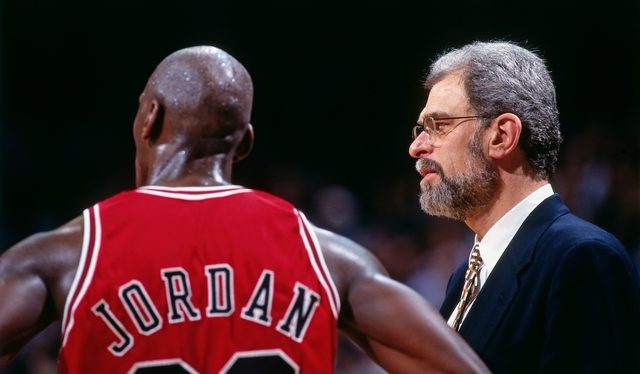

Jordan, over the first seven years of his career, had established himself as one of the most dynamic scorers in the game. Of all the things he had accomplished, there was one thing he had yet to do: Win the NBA Finals. His Bulls were one good quarter away. Phil Jackson huddled his team together. What he proceeded to share would epitomize what he tried to instill into a Bulls over the past several seasons.

In the past, Jordan had been Chicago’s main source of scoring. He had the ball the most, took the most shots, and scored the most points – but failed to involve the other four players on the floor. His efforts looked great in the box score, but they were never enough to win the last game of the season. Until now.

Throughout the series, Jackson noticed a glaring tendency: When Jordan would cut to the basket, Magic Johnson would often leave his man – John Paxson – and provide reinforcement to prevent Jordan from getting an open shot. Seeing Paxson was being consistently left wide open, Jackson wanted to take advantage of this.

He turned to Jordan in the huddle and asked, “Who’s open?” Jordan said, “Paxson.” Jackson, knowing he would say this, told Jordan, “Get him the ball.”

Just under four minutes remained.

The score was tied up at 93. Chicago had not recorded a field goal in the last three minutes of play. Jordan crossed over to his right at the top of the key, but was doubled by Johnson – leaving Paxson open. He dished it off to Paxson, but Johnson closed and Paxson pump faked. He threw the ball in to center Bill Cartwright, but his shot was blocked. Cartwright recovered and got his miss, dishing it back to Paxson. Paxson side stepped to the right and hit an eighteen foot shot. Chicago 95, LA 93.

On the ensuing possession, Cartwright grabbed the rebound off a Nick Perkins miss. He dished to Pippen, who then passed the ball to Jordan. Jordan pushed the ball up the floor, drawing three LA defenders into the paint. Paxson was left all alone in the opposite corner. Seeing this, Jordan stopped and threw a pass across the court to Paxson. He caught it and pulled up in stride, sinking the eighteen footer. Chicago 97, LA 93.

With two minutes remaining, LA trailed 101-96. Paxson brought the ball up the court. He passed it in to Cartwright at the top of the key. Jordan rolled over the top, looking for the hand off. Three LA defenders swarmed to Jordan, expecting him to take the ball from Cartwright. He didn’t. Cartwright faked to Jordan and passed it off to Paxson, who was wide open just inside the three point arc. Paxson stepped up and nailed his seventh field goal of the evening. Chicago 103, LA 96.

A little over a minute remained. Chicago’s lead had been cut to two, thanks to a Perkins three point play. The crowd was back on its feet, cheering for one more stop. Pippen dribbled the ball at the top of perimeter. Jordan screened for Pippen. Drawing a double team, Pippen dished the ball to Michael. Seeing a lane to the basket, Jordan drove towards the paint. He was met by two defenders. Johnson, yet again, had left Paxson wide open on the wing. In the past, Jordan would have forced the shot. This time, he dished to Paxson who hit the wide open jumper. Chicago 105, LA 101.

Chicago would add three more points before the final buzzer sounded. Final: Chicago 108, LA 101. Chicago had finally won its first ever NBA Championship. Over the next seven seasons, the team would win five more.

Largely, because of what Jordan learned during that 1991 season.

…

I remember my first summer of coaching like it was yesterday.

At the time, I was 19 years old. I had just finished up my freshman year of college. I was looking for summer work. I had always had an interest in coaching. When I had the opportunity to coach a team at the facility I used to train at, I jumped at the chance. I loved to teach and I loved working with kids, so I thought it would be the perfect summer job.

And then I saw my team.

To give you some perspective, my team was playing in the 11U bracket. Our facility also had a 10U team. Before our first ever tournament, we thought it would be a good idea for the two teams to scrimmage each other. My team lost by 15. In five innings. In our first tournament, I think we got out scored 48-4. You held your breath any time the ball was put into play. Throwing strikes was a luxury. Offensively, we relied on walks and hit batsmen. I’d say errors too, but that meant you actually had to put the ball in play.

I had been a part of some pretty bad teams before, but this one was beyond bad. Somehow, only being able to practice once per week, I had to figure out how to win games with a group of kids that might not have been able to compete at the 9U level. We had two more tournaments scheduled that summer, but I knew they would be a waste of time. As a result, I had to make the difficult decision to cancel those tournaments.

While playing games was not in our best interest, cancelling them indefinitely was a tough sell. These parents thought they paid for games. I wanted to play games as bad as they did, but I knew this team needed a lot of time, work, and patience. This didn’t sit well. Our two best players quit. Our practices typically had around six kids. We started with thirteen. My assistant coach was constantly up my ass because our practice time interfered with his Sunday family dinners. It was a shit show, but it was now my shit show. With nothing else to do, I did the only thing I knew how to do: I coached.

Over the next several months, we practiced once per week. I drilled them on the fundamentals of playing catch. We talked about glove positioning and how to play through a ground ball. We broke down situations and understanding where to go when the ball was hit in play. Footwork for each base was covered. We’d stretch our abilities and make difficult plays – turning two, diving in the hole – you name it. Our kids might not have been great players, but it wasn’t going to stop me from challenging them to make great plays.

Outside of practice, each kid was given homework – and it wasn’t just physical homework. These kids needed to learn and appreciate the history of our game. After each practice, I would assign one player for the kids to research and learn about. These players ranged from Lou Gehrig and Jackie Robinson to Jim Abbott and Roberto Clemente. I didn’t want kids to treat baseball practice as a once per week thing. I wanted them to build a love and appreciation for the game. If you love it, you’ll put everything you have into it – which is all I ever asked for.

I didn’t ask for talent. I asked for hard, honest work.

…

At the end of the summer, I decided we had earned one last scrimmage against the 10U team before I went back to school. In our first contest, the game had been over after the second inning. In this contest, we were down one run going into the fifth inning. One young man threw a complete inning after failing to record an out in our first tournament. Another had a two RBI single off one of the best pitchers on their team. I’ll never forget seeing that smile when he stood on second base.

While we couldn’t quite pull it off at the end, I could not have been more proud. I faced a ton of criticism throughout that summer. Parents thought I was crazy for cancelling games. Practices weren’t well attended. The kids that did show up were challenged. Most days were better than others. I felt like I was in an impossible situation destined to lose.

And then I remember getting a specific email from a parent.

We had just wrapped up our last practice. I was a few days away from moving into college to start my sophomore year. The email was from the mom of one of our kids. Over the course of the summer, I taught him how to play first base. Largely, because he was left handed and he wasn’t quite the best at catching fly balls. And we usually didn’t have numbers at practice, so we often needed a left hander who could only play first base.

Apparently, this young man had not been able to play first base before this summer. He was often pushed to the outfield on his other teams, but he had always wanted to play first. His mom thanked me for giving him the opportunity to do so, saying it meant a great deal to her and her son. He had never gotten a chance to show what he could do. I was the one who finally gave him a chance and had the patience to work with him. I never thought anything of it. If a kid wanted to work and learn, I was going to teach him.

I haven’t forgotten that email to this day.

That summer as a head coach for the first time ever taught me a ton about who I am as a coach. When faced with external pressure, I had the courage to make an unpopular decision and stick to a process I believed in. I wasn’t dejected when it didn’t happen on my time. I was patient. I gave kids the room to work, learn, and push through challenges they had never faced before – which ultimately had a profound impact on one specific kid. That was enough for me.

When in doubt, I defaulted to the thing I know and love best: Teaching. My role there, in my eyes, wasn’t to win medals. It was to teach the game of baseball – inside and out. We lost a fair amount of kids and parents because of this, but those never really concerned me in the first place. They wanted to win now. I knew we couldn’t win now, so I exercised patience and played the long game.

Which is exactly what Phil Jackson needed with his best player back in 1991.

…

In the mid 1950’s, Tex Winter brought a system to college basketball the game had never seen before. The system, initially established by Hall of Fame USC basketball coach Sam Barry, was largely implemented out of necessity. At the time, Winter’s Kansas State basketball team had struggled to match up against teams like Wilt Chamberlain’s Kansas Jayhawks and Oscar Robertson’s Cincinnati Bearcats. Seeing a need for innovation, Winter decided to adopt and evolve on Barry’s work at USC.

We know it as the triangle offense.

The triangle offense was designed to get all five players on the floor involved through motion. When the ball entered the half court, a key pass at the elbow would start the sequence. Off that pass, players could move, flow, and create in ways that suited their strengths. The resulting movement would resemble a series of triangles throughout the floor – low post, high post, and wing, for example.

The goal of the system was to eliminate one on one basketball and instead encourage movement from all players throughout the entire floor. Defensively, you couldn’t focus and distribute your efforts to one person. You had to be accountable for all five. If you were not, the offense could create desirable scoring outcomes through consistent motion and screening.

Winter used this system to take Kansas State to the Final Four during the 1958-59 season. Their 25-2 record still stands as the best season in school history. After guiding Kansas State to seven different postseason trips and one more Final Four in 1964, Winter was hired by the Houston Rockets in 1971. After a brief stint with the team, Winter returned to the NBA as an assistant for the Chicago Bulls. The year was 1985. Just one year prior, the team drafted a young man from North Carolina with the third overall pick. His name was Michael Jordan.

While Winter tried to instill the triangle offense to then head coach Doug Collins, he was quickly met with resistance. His stint with Houston was largely a failure. He had only achieved sustained success at the collegiate level. Many thought his triangle offense was not good enough to translate to the NBA level. Instead, Collins put Chicago’s offense in the hands of its young star Jordan. Winter was banned from the bench.

Jordan had developed into one of the game’s most prolific scorers, but he had not learned how to take down Detroit all by himself. In 1988 and 1989, Chicago was eliminated by Detroit’s “Bad Boys” – lead by Hall of Fame guard Isaiah Thomas. In five years Jordan had a lot of impressive box scores, but zero trips to the NBA Finals. General Manager Jerry Krause knew he had to make a change. Krause fired Collins at the end of the 1989 season – despite making a trip to the Eastern Conference Finals.

To replace him, he promoted assistant coach Phil Jackson. Winter would regain access to the bench and remain on staff, where he worked with Jackson to bring the triangle offense to Chicago. They didn’t care if Jordan lead the league in scoring. They cared if they won the last game of the season, which ultimately created friction that plagued Chicago throughout much of the 1990 season.

Jordan might have been a tough sell, but Jackson knew what would happen if Jordan decided to do it his way. It was time for a different way.

…

After a devastating game seven loss to Detroit in the 1990 playoffs, Jordan had a change in demeanor. He had spent so much time and energy challenging and pushing himself over the past seven years. He had zero championships to show for it. Detroit had proven it was too much of a challenge for Jordan to take on himself. He needed help. He couldn’t just push himself to the limits. He had to learn how to push and lean on his teammates.

When Jackson and Winter first introduced the triangle offense, Jordan was less than thrilled. Anything that took the ball out of his hands did not make sense to him. He felt he had earned the right to have the ball more than anyone else. Jackson recognized how special Jordan was, but he knew how easy it was to game plan against a one man show. The tough part wasn’t putting the system together. It was the patience and persistence required to get Jordan to believe it would work.

This was arguably the most important lesson I learned from my first summer as a coach.

While I wasn’t working with multimillionaires, I was working with a group of kids and parents – who didn’t choose me – that had different desires, personalities, and motives. Getting them aligned down a route I believed in was not easy. It required some selling, but it largely required patience. If I wanted to teach these kids, I had to be willing to go through a lot of bad days. Our practices were not glamorous. We screwed up a lot of stuff – myself included. Things you once took for granted all of a sudden become the things you spend the majority of your time coaching up. The simple act of catching and throwing a baseball was coached constantly. There were no details. Everything mattered, which made it frustrating when at times it seemed like nothing mattered.

If I knew one thing, I knew this: I didn’t care if we won any trophies that summer. If my kids were going to say anything about me, they were not going to say that I didn’t coach them hard. We were going to learn the game the right way. I didn’t care what parents thought or if they decided our plan to practice all summer was stupid. I believed in what we were doing. I knew if I was patient and stuck to my plan, we would see the fruits of our labor in time.

Jackson encountered similar resistance in Chicago when implementing his new system with Winter. After observing the Bulls from the bench over the past several seasons, he knew how important the triangle offense was going to be to get everyone involved on offense. They couldn’t constantly rely on Jordan, but they also needed to keep him happy. This was difficult. Jordan was not one to trust others with the ball, but Jackson was not one to give up on something he believed in strongly. He knew if he exercised patience and persistence, Jordan would see his system through.

This finally became evident during the 1991 playoffs.

Before their date with Detroit, Chicago had to take care of Charles Barkley’s Philadelphia 76ers in the Eastern Conference Semifinals. Philadelphia, in a lot of ways, resembled Jordan’s Bulls from a year ago. The majority of their offense went through standout forward Barkley – averaging 27.6 points per game and 10.6 rebounds per game in 1990. Jordan recognized this. Barkley was a great player, but Jordan knew he couldn’t beat the Bulls along. Largely – because that’s what he tried to do in the past.

When Barkley’s 34 point effort was not enough to knock off Chicago in game one, Jordan said, “It’s a total reversal of what we used to be. I’m familiar with that, because you’re a competitor and you try to carry the load. But sometimes you’ll come up short. If Charles continues to score half their points, we’ll win.

“You’re bound to get tired when you have to score and rebound and play defense. I know. I’ve been there.”

Philadelphia’s four starters not named Barkley combined for 17 points. Chicago’s four without Jordan combined for 52.

…

Our most important battles will not be a testament of brute force and will, but of patience and persistence. If you find something you believe is worth the wait, do not waiver in your efforts. Any profession that deals with people lives in the gray area. We are constantly working to gain influence, build trust, and create change within the populations we seek to teach. You will not win many of these battles in one day. They require time.

That summer will always influence how I coach players going forward because of the patience I learned. I didn’t choose those kids and they didn’t choose me, but they showed up to work. As long as they did, I was going to also. It didn’t matter where we stood. It only mattered if we could look back and say we got a little better than we were the day before. When you compound a lot of these days over a period of time, you have the opportunity to look back on something pretty cool.

Jackson’s triangle offense wasn’t built in one day. It took nearly two years before his players believed it would take them to a place they had never been before. He didn’t give up on it because it was met with resistance from his best player. He learned how to make him his ally by showing him how he could still be great using a system that made everyone else great. Jackson’s patience bought him enough time for Jordan to see it through.

Don’t give up on it because you can’t see it. You owe it to yourself to do what you believe in – even if everyone else does not..

yet.